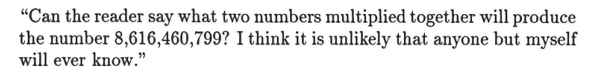

Let’s factorise a big number, Jevons’ number, a number from 1874 held up as practically impossible to factorise…

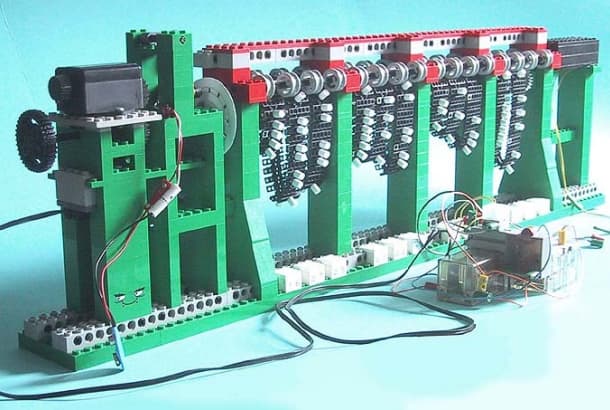

Here’s a Lego approach to Lehmer’s sieve, from Uli Meyer’s informative pdf:

Reconstruction of D.H. Lehmer’s number theory computer with LEGO®

Here’s Lehmer’s paper from 1928:

The Mechanical Combination of Linear Forms

In 1996 Solomon Golomb showed how even in Jevon’s time the problem might have been solved in a matter of hours, by careful thinking and a certain amount of calculation. Golomb himself used a 10 digit calculator with a memory and a square root function and got it done in 6 minutes.

Of course I’m a fan of Lego, and I could have been a fan of Fischer-Technik if I’d had enough of it…

I’m pretty sure I’ve read of Turing surrounding himself with brass wheels constructing a prime number sieve… (but it turns out I’m wrong…)

The second problem that Turing investigated on the Manchester Mark 1 was the Riemann Hypothesis (or RH), which has to do with the asymptotic distribution of prime numbers.

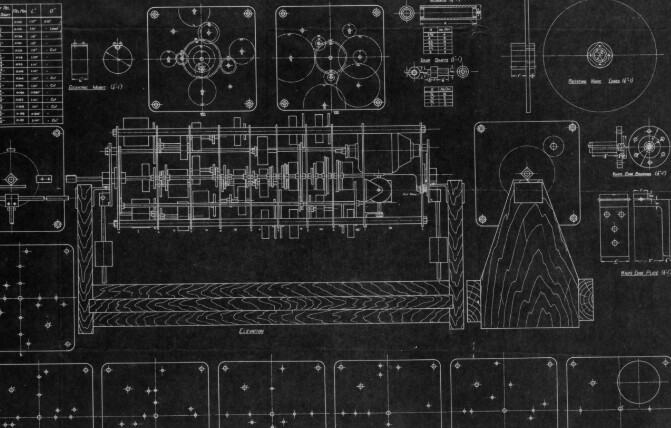

This was a problem close to Turing’s heart, and in fact he made an earlier attempt to investigate RH in 1939 with a special-purpose analog machine, using an elaborate system of gears. Turing had apparently cut most of the gears for the machine before he was interrupted by the war. By the time that he returned to the problem, in June of 1950, the progress toward general-purpose digital computers during the war had made Turing’s 1939 machine obsolete. (The machine was never completed, though we do have a blueprint for it up by Turing’s friend Donald McPhail. A project has recently been proposed to build it; ironically, the first step of that undertaking will be a computer simulation.)

- from TURING AND THE PRIMES by ANDREW R. BOOKER

Here’s that blueprint on the web:

And from this discussion of it, we read about Turing’s first project, in 1937, a binary multiplier:

my small contribution to the project was to lend Turing the key to the shop, which was probably against all the regulations, and to show him how to use the lathe, drill press, (etc.) without chopping off his fingers. And so, he wound the relays; and to our surprise and delight the calculator worked.

and his second, this Zeta function machine, which is prime-related but as it turns out not related to factorising… oops.

Alan’s zeta function computer was a device for adding up a large number

of sines and cosines of various periods and amplitudes… The gears, of which there were to be hundreds, were to provide an approximation to the required periods… Alan obtained rational approximations to [the periods]… by the method of continued fractions. A pair of gears having the number of teeth indicated respectively by the numerator and denominator of the fraction would then rotate at speeds having approximately the desired ratio.”

(via Thomas Puettmann on hpmuseum forums)

![The quantum computer of 100 years ago – Factorize[8 616 460 799] – fischertechnik Lehmer sieve](https://img.youtube.com/vi/-gBhDNJqEE8/maxresdefault.jpg)